Servitisation in construction

|

| Advantages of servitisation |

Contents |

[edit] What is servitisation?

The concept originated in manufacturing and much of the research about servitisation focuses on manufacturing companies. Servitisation is the transformation of a firm from a product-centric approach to a service-centric approach. In doing so, the firm shifts its business model to improving customer value in use, thereby assuming greater responsibility for the overall value-creating process as compared to product-centric, transaction-based business models [1].

Probably the most significant example of servitisation is the successful transformation of IBM in the 1990s from a product-centric to a service-centric organisation.

Although IBM first released its personal computer to the market in 1975, sales were disappointing as there was low demand for computers. It was not until 1980 that IBM tried again to crack the personal computer market [2]. By then many other companies were already making the machines, and IBM was not able to gain immediate control of the market.

In 1994, new management led IBM to exit the network products business, focused on application software, storage and personal computers to become a freestanding service-business focused on software.

As of 2018, IBM is an US$80bn company and number one in many areas of the industry, including enterprise services, enterprise security and artificial intelligence.

Advantages of servitisation

Research suggests that servitisation can nurture growth and profitability in different ways.

- First, higher revenue potential often exists in industries with an extensively installed product base, such as the aerospace, locomotive and automotive industries. Service revenues can be one or two orders of magnitude greater than new product sales.

- Second, as services provide a steadier source of revenue, increasing service revenues can compensate for declining revenues in equipment sales. And adding a service offering to your products makes them less sensitive to price competition.

- Third, services are globally more profitable. Due to their lower price sensitivity and lower comparability, service offerings tend to offer higher margins and rates of return than basic products [3]

However, these advantages are not universal and the success of a firm’s servitisation journey is highly dependent on its strategy and several other factors.

As an example, here are three servitisation strategies:

- Added services – where a manufacturing firm remains primarily a product provider but with some service proposals integrated into its offerings.

- Activities reconfiguration – where the manufacturing firm defines itself as both a product and service provider and actively creates value by developing new activities with its customers.

- Business model reconfiguration – where the provider no longer transfers the ownership rights of its products to customers. Instead, its offerings are sold on ‘by use’ or ‘by results’ basis.

|

There are many other servitisation strategies out there, these examples just illustrate the concept.

[edit] Challenges of servitisation

Moving towards higher levels of servitisation carries the following risks:

- Resource shortages to deliver the service.

- Reduced focus on product improvement and of management failure of the complexity of processes coordination – firms may struggle to coordinate multiple services and products offerings.

Servitisation transformation is also costly and does not necessarily bring immediate return on investment.

Customers often have a service-for-free attitude which makes it even more difficult to develop a sustainable business plan for this investment.

|

Success factors, based on the analysis of success stories like the IBM transformation, do not lay solely with capabilities for investment.

Top management sponsorship and employee involvement are the top two factors, while monetary and other incentives come last on the list [4]. The necessary cultural changes include a mental shift from selling a product to thinking about the customer’s needs, basing decisions on data and facts, moving from relationship-driven approaches to performance-driven ones, and increased accountability and transparency.

[edit] Servitisation in the construction industry

Facilities management is a good stand-alone example of servitisation which has been around for a long time, with the desired service outcome being building availability and regular maintenance.

This is a form of ‘outcome-based contracting’ even though in this case the outcome may not be a particularly ambitious one, i.e. that the building remains operational.

There are other examples, notably façade manufacturers who routinely provide detailed design services that engage their own supply chain and allow them to take full control of what is admittedly quite a specialist service.

However, on a building-as-a-product level, servitisation still has a way to go.

For a long time, BSRIA, CIBSE and other organisations have been arguing in favour of building performance evaluations and other ways of measuring how the building performs once handed over, compared to its design intent. In other words, a performance-based delivery for the building rather than a product-based one.

There are numerous barriers to building performance evaluations becoming a delivery standard and this article will not elaborate on them here, focusing instead on where the future might lie for servitisation in the construction industry.

|

[edit] The future

Two terms are probably key to better understand the way forward:

If servitisation is the customer-led pull towards value creation, Industry 4.0 is the technological push, with IoT being the enabler of this phenomenon [5].

If servitisation is all about thinking like the customer, aligning with the customer’s needs and offering a service that provides value and changing our business models and behaviour to suit, Industry 4.0 is about figuring out how the firm can harvest the benefits of this closeness with their customers to improve their own systems and processes.

The relevance of servitisation for the construction industry can be explored in the facilities management area, where remote sensing can be used to monitor environmental conditions and signal when systems are not operating optimally. In real estate management and architecture, spatial optimisation can be used to save floor and desk space, and internal environmental quality monitoring can improve health and wellbeing and can indirectly even affect productivity. BIM and digital twins can affect asset management – the list is quite extensive.

With technology now enabling easier and cheaper data gathering and data availability, built environment professionals can continuously monitor the performance of assets and feed data back to asset owners, designers, manufacturers and building operators.

With an increasing ability to measure performance, there is an increasing interest from building occupants in the performance of their buildings. CBRE’s Occupier Survey shows that 92% of companies they surveyed have a preference for wellness-capable buildings, 67% see productive and flexible workspaces as vital to achieving their goals and 56% see user experience and productivity as key reasons for future technology investments [6].

All of this leads us towards defining buildings as a set of outcomes, rather than a collection of building products, i.e. the building as a set of service offerings, with service providers continuously monitoring the performance of their service and optimising their offer based on learnings from their portfolio.

How would this work? Who would operate such a building? Who would take ultimate responsibility for the overall performance of the building? There are lots of questions that a topic like this elicits and no doubt, built environment professionals will be involved in answering them as the demand grows. Industries have evolved and customers are changing. Change – even disruptive change – is necessary and inevitable in order to allow the construction industry to embrace it, and move towards a more circular, service-based and ultimately more sustainable built environment.

[edit] References

- [1] Kowalkowski, C. Servitization and deservitization: Overview, concepts, and denitions. Industrial Marketing Management 60 (2017) 4-10.

- [2] Ahamed, Z et al. The Servitization of Manufacturing: An Empirical Case Study of IBM Corporation. International Journal of Business Administration 4 (2013).

- [3] Ambroise, L et al. Financial performance of servitized manufacturing rms: A conguration issue between servitization strategies and customer-oriented organizational design. Industrial Marketing Management 71 (2018), 54-68.

- [4] Ahamed, Z et al. The Servitization of Manufacturing: An Empirical Case Study of IBM Corporation. International Journal of Business Administration 4 (2013).

- [5] Frank, Alejandro G. Servitization and Industry 4.0 convergence in the digital transformation of product rms: A business model innovation perspective. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 141 (2019) 341-351.

- [6] CBRE EMEA Occupier Survey, 2018.

[edit] About this article

This article, originally titled ‘Servitisation: an opportunity to grab with caution’, was written by Eszter Gulacsy and previously appeared on the BSRIA website in January 2020. It can be accessed HERE.

Other articles by BSRIA on Designing Buildings Wiki can be accessed HERE.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Artificial intelligence.

- Big data.

- BSRIA articles on Designing Buildings Wiki.

- BSRIA.

- Building Services Analytics - BG 75 2018

- Business-Focused Maintenance BG53 2016

- Digital technology.

- Digital twin.

- Internet of things.

- Soft landings and business-focused maintenance.

- Servitisation, smart systems and connectivity of instrumentation.

--BSRIA

Featured articles and news

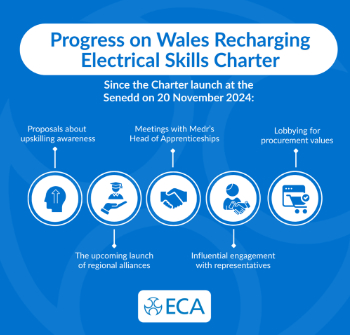

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.